by Mike –

The article about the Spohn Convertible that I said was ugly created a small controversy. Some readers left comments taking exception to my description. I wrote that this car was so ugly that I couldn’t look away.

I found the following history summary of Spohn written in 1974 and originally published in Special Interest Autos, January-February 1974.

It was posted on Forgotten Fiberglass in October 2011.

______________________________

by Michael Lamm and Erik Eckermann (Munich)

Carosserbiebau Spohn became one of those rare European coachbuilders who managed to survive World War II. Spohn did this by building direction finders for the Wehrmacht during the war and after the armistice, repaired military vehicles briefly for the occupying French.

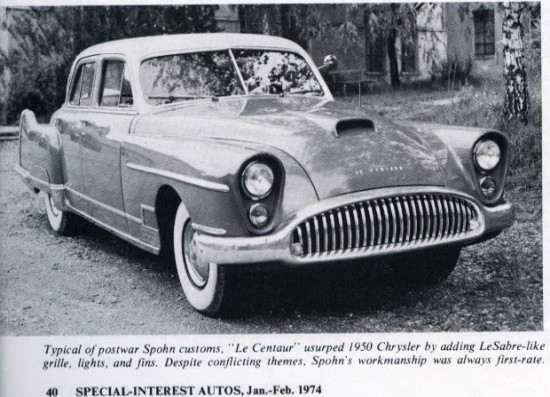

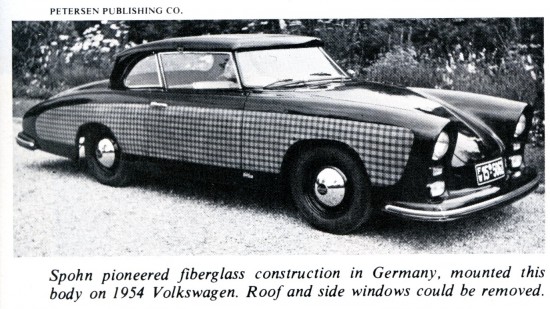

After that, Spohn returned to coachbuilding and catered mostly to American GI’s. One postwar correspondent called Spohn “the George Barris of Ravensburg.” Another observed wryly that Spohn’s rather unrestrained, often bizarre creations were “the revenge of the Third Reich”, especially in view of a spate of grossly overdone GM LeSabre-copying fins and front treatments.

A number of Spohn’s postwar customs seem almost like spoofs of American styling themes of the early 1950’s. Behind these odd blendings of lines and motifs stood a company with a reputation and background as solidly respectable as the Bank of Hanover. Carosseriebau Spohn was founded in 1920 by Josef Eiwanger and Hermann Spohn as equal partners in a Ravensburg body repair shop.

Spohn died in 1923, but Eiwanger enjoyed building custom bodies more than straightening bent fenders, so it didn’t take long before he and his staff were hammering out full coachwork on Bugatti, Mercedes, Steyr, Opel, and Maybach chassis.

In 1929, Carosseriebau Spohn became a favored coachbuilder for Maybach, a relationship that flourished until 1939. Josef Eiwanger acted as Spohn’s chief body designer and engineer. One of Eiwanger’s best-known creations was the flush-fendered Maybach displayed at the 1931 Berlin Salon.

This car was far ahead of its time and appeared two full years before the 1933 Pierce Silver Arrow. Another Spohn blockbuster came in 1935, again on Maybach basics – a streamlined design built along Jaray patents, with blended fenders, a curved wrap-around windshield, and a highly streamlined overall shape. Both cars caused quite a stir among automotive designers in Europe and the United States.

Josef Eiwanger Sr. retired during WWII, and in 1945 Josef Eiwanger Jr., son of the founding partner, was put in charge of Carosseriebau Spohn by occupying French forces. The Spohn plant at that time consisted of approximately 21,500 square feet of covered area. After the German currency reform of 1948, Spohn returned to building custom bodies but since Europeans – even European noblemen – had no money to spend on coachbuilt cars at that time, Spohn’s customers became mostly American GI’s stationed in Germany.

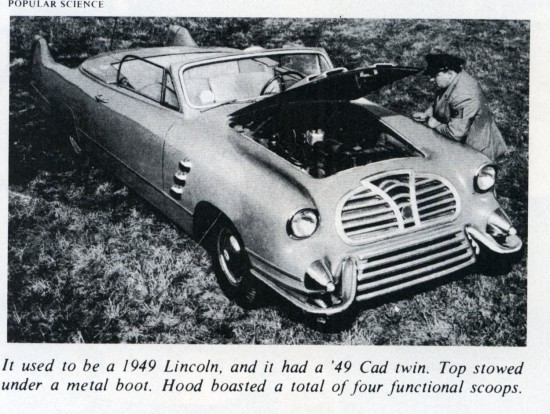

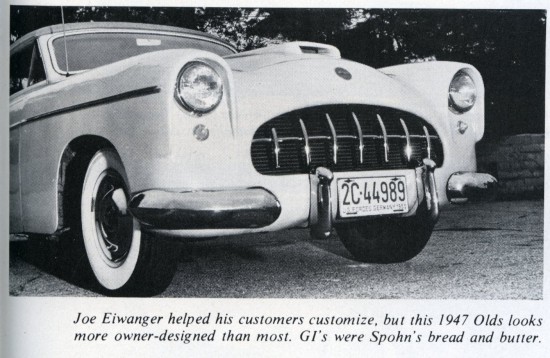

The practice of backyard customizing was becoming popular then, especially in California, and Spohn was happy to accept the title of Ravensburg’s Kustom King. Most of Spohn’s prewar craftsmen had returned to the company, so technique was no problem, and labor was quite inexpensive. Josef Eiwanger Jr. soon became known simply as “Joe” to his customers in uniform. Joe was eager to please, and he knew better than to quibble with some of their more unusual demands – the tailfins, portholes, expanses of chrome, heavy bumpers, and the like.

In fact, Joe Eiwanger soon found himself helping his GI customers design their cars, and he did this with the aid of a fairly standard “box of toys”. This consisted of preconceived items and themes – amps, bezels, handles, plus fairly standardized grille treatments, moldings, spinners, bumpers, the shapes of decklids, hoods, roofs, and interiors.

Any of them could be adapted to a variety of cars. Spohn craftsmen, having built these standardized items a number of times before, could do so again more quickly and at less cost.

The “box of toys” approach explains why so many Spohn customs share specific features and why the individual components sometimes don’t mix and match too well aesthetically.

But very often the GI patrons insisted on these conflicting themes. Spohn occasionally modified stock designs with only minor revisions, in which cases the tabs came to a few hundred dollars. Too, Spohn enjoyed a deserved reputation for fine paint jobs, so many GI’s took their cars to Ravensburg simply to have them repainted.

A full custom body, though, might cost anywhere from $3000 to $7000, depending on how much work was involved. A Mercury custom that Spohn finished in 1952 is perhaps typical. The car was commissioned by an Army captain in 1950. The captain had bought a brand-new, unbodied Mercury chassis from Ford’s Belgian assembly plant for $1100.

Spohn’s bill for the scratch-built body came to $6000. The captain, by the way, sold his car late in 1953 in this country for $3800. Another example and perhaps an extreme one involved Charles (Chuck) Justice of Gainesville, Virginia. Mr. Justice was not a GI, but he wanted a Spohn body on his 1947 Cadillac anyway. He had to pay full fare to ship the car back and forth between Virginia and Ravensburg.

He did all his designing by correspondence, waited one full year for the finished product, and paid a grand total of $14,101. More usually, GI’s would have Spohn customize the cars they had brought with them on their tours of European duty. Uncle Sam footed the bill for shipping both ways at that time. So while they had them there, many GI’s decided to let Spohn give their cars that unique Teutonic touch. This decision was sometimes prompted after an accident, when the cars needed surgery anyway.

Spohn and Veritas Automobilwerke

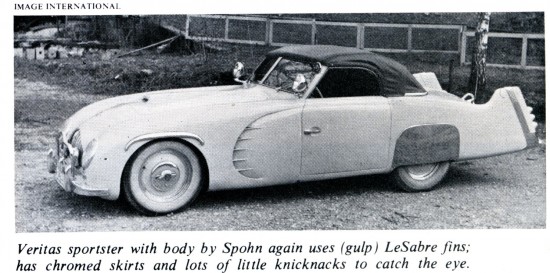

At the same time that Spohn was building one-offs for GI’s, the company was also turning out bodies for the newly funded Veritas Automobilwerke. The Veritas sports car was established in 1946 by former BMW employees, and it survived as a make until 1953. Spohn built a dozen or so custom bodies for Veritas, as did Baur of Stuttgart – far-out open jobs, sometimes with Spohn / LeSabre-type fins.

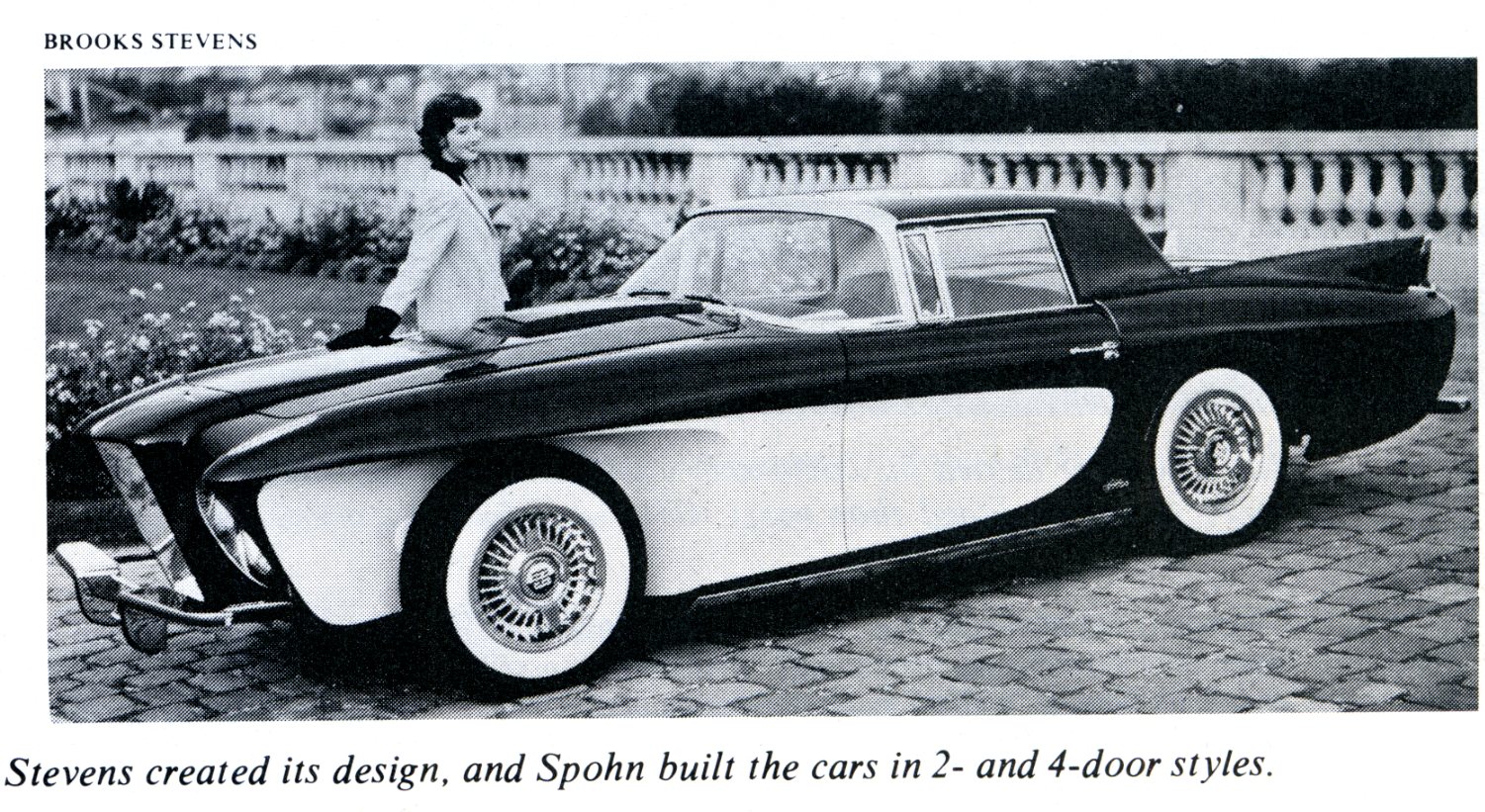

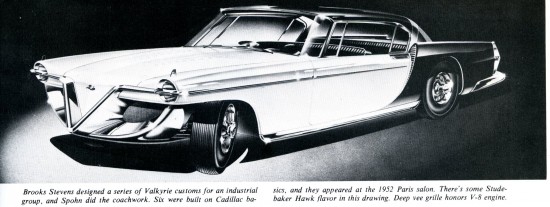

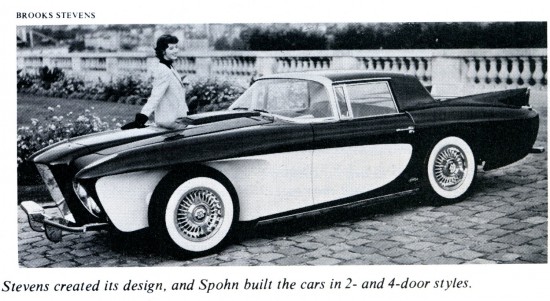

Brooks Stevens, the famous Milwaukee car designer/collector, commissioned Spohn to build two “series” customs of half a dozen cars each. These were the Valkyrie, conceived in 1952 and shown for the first time at the 1954 Paris salon, and the Gaylord, which bowed on the same stand in 1955. An industrial group funded the Valkyrie project. Six cars were built on Cadillac basics. The Valkyrie pioneered such innovations as a removable forward roof section, rollbar accent, combination grille/bumper, and 2-tone black-and- white exterior.

“The car was controversial from the critic’s standpoint,” says Brooks Stevens, “but it was given a great deal of publicity. I had one built for Mrs. Stevens in 1955, and we still have it.” This car, along with an impressive array of antiques, classics, and customs is on view at the Brooks Stevens Automotive Museum in Milwaukee. The other Stevens-designed, Spohn-built series custom was the Gaylord. The Gaylord family of Chicago, whose fortune rested on the invention of the bobby pin, wanted to launch a lush, limited-production sportster in the classic vein.

Brooks Stevens designed the car, and Spohn built six in 2 and 4 door configurations. Frames were tubular, and Gaylords were powered by Chrysler hemi V-8s coupled to GM Hydramatics. Touches included a pull-out rear drawer for the spare, illuminated fender wells for nighttime tire changes, retractable hardtops, and dashboard dials angled toward the driver. At their projected price of $10,000, Gaylords would have been considered bargains.

Spohn constructed one-off postwar custom bodies on every imaginable make and model of U.S. chassis, from 1940 Buicks to brand-new 1953-54 Cadillacs, Packards, Olds, and Chryslers. It made no difference to Joe Eiwanger. His Old World craftsmen, some of whom had come aboard in his father’s day, lavished the same coachbuilding finesse and detail onto these over-enthusiastic traffic stoppers as into the magnificent Maybach V-12s of yore.

Carosseriebau Spohn closed its doors forever in 1957, at which time its assets were liquidated. Josef Eiwanger took an engineering position with Mercedes-Benz, and he retired a few years ago to return to Ravensburg.

Note from SIA: Our tanks to Josef Eiwanger, Ravensburg, West Germany; Erik Eckermann, Munich; Strother MacMinn, Los Angeles; David S. Henderson, Vienna Va.; Charles Justice Gainesville, Va.; and Brooks Steves, Mequon, Wisconsin.

Let us know what you think in the Comments. The Spohn Convertible below started this conversation.

This was first posted here in December 2015.

Mike, your readers may be interested to know that the prototype Gaylord has finally been purchased from the Gaylord family. It is now in Glendale, Ariz. I can provide contact information to serious potential buyers if they call me on 310 927 4976

David Mulvaney

When Spohn Customs are discussed there is a common mistake made: the styling is attributed to Spohn. The car owners chose what ideas and elements they wanted included in Spohn’s build of their cars. Spohn had photos sketches of their own and others special builds and the owner said I’d like this and that and some of those. Thus the finished products can look incongruous in many cases. Don’t blame Spohn for “the customer is always right”.

I own a Spohn Custom from 1952 based on a 1940 Ford chassis and it is well along in restoration. It has received numerous compliments and is unique

The revenge of the Third Reich, INDEED !