by Wallace Wyss –

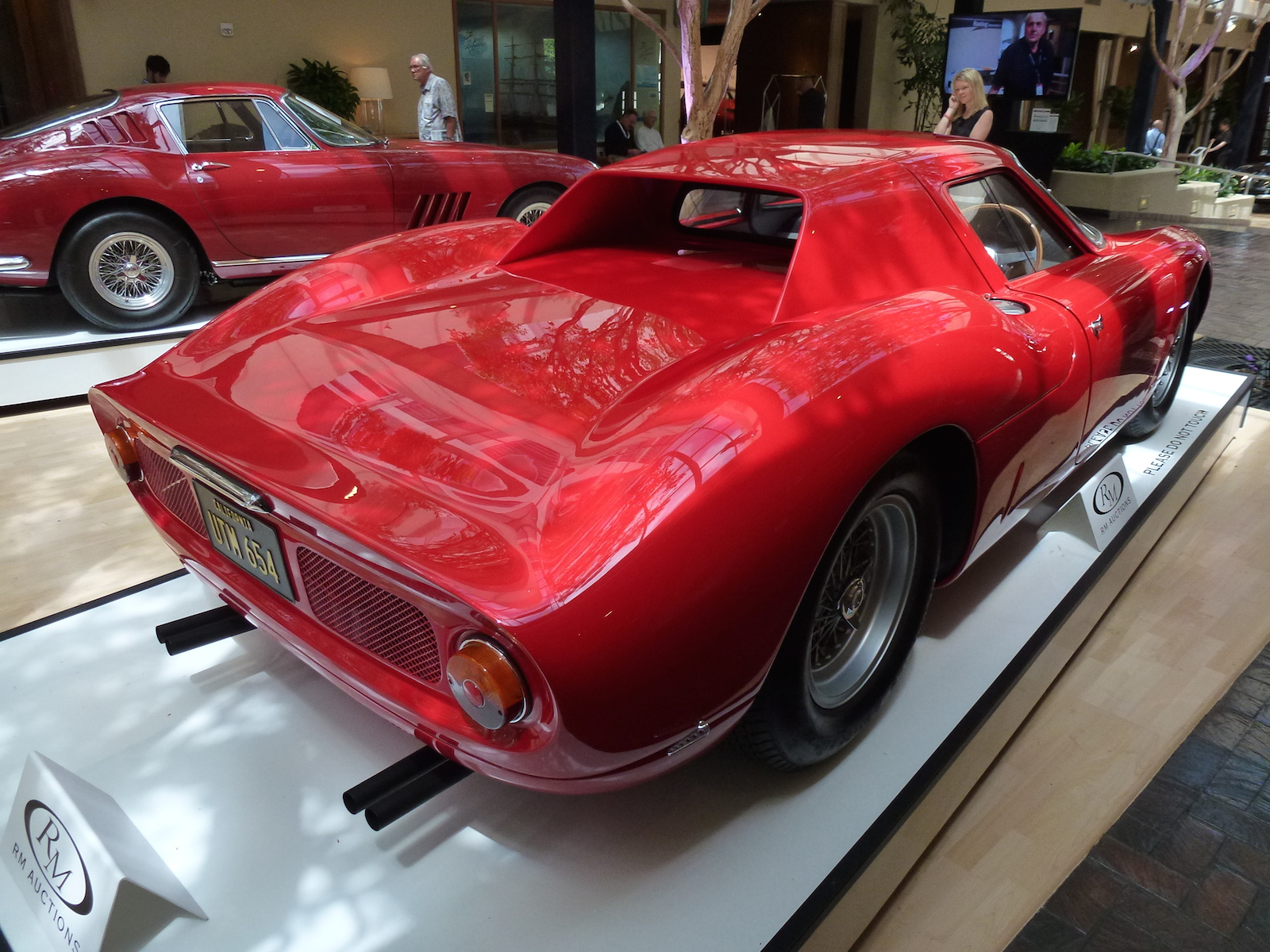

A lot of the cars I paint in oil on canvas I only have a scant memory of but some I’ve seen in person. When I first moved to California to stay (having worked the summer of ’65 for Motor Trend) in 1970 I started attending Ferrari Owner’s Club events and at least one owner had a 250LM that he took on Malibu Canyon runs. It was incredible–a full LeMans racer and yet it was a hobbyist’s car. I think it went off a Malibu cliff at least once.

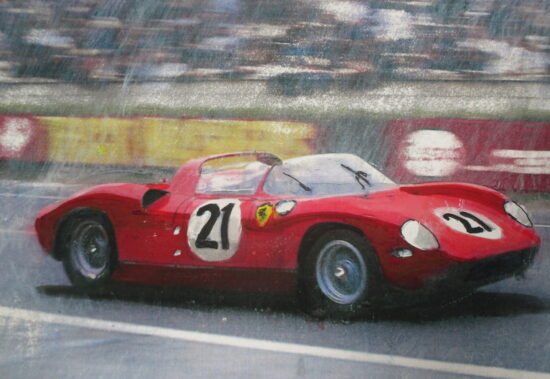

So my own interpretation of 250LM history is hazy but why I like the car is the LeMans victory story. It was entered as a used car by a private racing team, Luigi Chinetti’s North American Racing Team yet beat the factory team. Chinetti not only won LeMans himself as a driver in ’49 in a barchetta and put the firm’s name on the map but for several years funded his own team to promote Ferraris in America.

Of course everyone had assumed, considering the millions Ford was pumping into LeMans after they fell flat in ’64, Ford would win. For ’65, Ford had entered two big block 427 Ford GTs and four small blocks as part of their factory team plus Shelby had some Daytona coupes (289 iron block pushrod engines) There were 11 Fords vs. 12 Ferraris as the starting flag fell.

But the factory P2 Ferrari prototypes had weak brakes as the rotors cracked. They went out. Ford lost the big blocks and then the small block GTs went out from overheating, caused by bad head bolts (that Ford insisted on changing though Shelby was opposed).

So by midnight no factory Fords, no factory Ferraris. In a way Ferrari didn’t want their dealer’s cars besting the factory team. They were worried their big sponsor, Dunlop, wouldn’t be happy if the Goodyear-shod Chinetti 250LM bested the Dunlop-equipped Ferrari factory cars. Some significant offers were reportedly made by Ferrari to Chinetti if he’d just slow his leading car down a tad. Rumors are two Ferraris and later four Ferraris. Not to drop out, just to let one of the remaining Ferraris on Dunlops win. But Ferrari was dealing with personalities.

His one time champion, Chinetti, had the taste of victory in his mouth. And yet Chinetti himself had a problem–driver trouble. Masten Gregory, the Kansas City Flash–had thick glasses and couldn’t see through the fog in the dark. He had come to LeMans to pilot a Maserati but a co-driver crashed it in practice. So he ended up in the 250LM. He came into the pits as night fell only to find co-driver Jochen Rindt missing. That’s when team friend and race car driver/car dealer named Ed Hugus volunteered to take the wheel. He’s not entered in the race! But he goes out for awhile until Rindt is found. Rindt had been bored silly with Chinetti’s rule to not go above redline and reportedly had been planning to leave mid-race, but he agreed to take the wheel again if he got carte blanche to drive his way–which was flat out, the hell with redline. Devil take the hindmost, and it worked.

As the celebration began, Hugus was missing but it would have been too controversial to bring him onstage. It was Ferrari’s last win at the Sarthe. I love this story because it demonstrates the innate competitiveness of an immigrant who didn’t bend under pressure…

Let us know what you think in the Comments.

FROM THE AUTHOR/ARTIST: The Ferrari 250LM prints of his paintings are available as 20″ x 30″ prints on canvas. Write malibucarart@gmail.com

Thank you Wallace. Great story and just totally completes my now breakfast morning with my alligator bodin and strong coffee while listening to theme song Shaft. These – yours stories like this is one of the most valuable parts of our love of cars. Cars come up for sale with, “this is a no story car”, apply that to any human and no would care and all would quickly run away. These stories give life, history, feelings, emotions and dreams to these beautifully noisy metal artworks that leak on the floor, vibrate out false teeth while trying to consume all monies all of the time even as it was real and felt that a wedding ring existed. The stories that came from the emotional automotive 60’s world are just priceless, I believe the “FERRARI VERSUS FORD” movie changed many peoples beliefs of our cars.

Thanks again! Jeff

I am posting this comment from Wallace Wyss…

Mike Gulett

Au Contraire, mon Frere…..

Contrary to my version, historian Doug Nye, author of many books on 20th Century long distance racing, says he doubts the Hugus claim of co-driving in ’65 at LeMans, Nye says Hugus had been promised a NART Ferrari to drive but, when he arrived at the track, discovered the car meant for him hadn’t been finished, Nye doubts Hugus could have driven a car he was new to that fast. Still, I met Hugus, who was 42 at LeMans in ’65, and I know of his war record (airborne) and his business record (he was Shelby’s first dealer) so I have no reason to doubt him. He was already a successful racer, having raced at Lemans 8 times previously, and a successful businessman. No reason to lie. (And, if you look at the victory lane photos where all the crew members try to climb aboard as the winning car heads for the Winner’s Circle, he’s quite prominent. So it remains a never-ending mystery. …

Hugus, the guy with the white hat in the attached photo

Maybe it’s because I became a car enthusiast in the ’60s when drivers’ faces were still mostly visible

that I identified with them more and guys like Dan Gurney and Phil Hill became my heroes, but I am more interested in their racing experiences than that of modern racers whose faces we can’t see because of full face helmets. Plus long after they were retired I’d meet guys like Phil Hill, Bob Bondurant Shelby or Gurney at various events, In working on my (three) Shelby books, I also got to meet crewmen like Phil Remington so I identify more with teams where I knew some of the participants. Plus cars from that era I got to see in person on the road when you could still drive a full fledged race car on the road, like a Perrari 250P, 250LM, 330P, or 250GTO , Porsche 906 and 908, etc.. I picked my era to commemorate in words and on canvas and I’m stickin’ with it.