Photos, captions and comments by Mike Gulett –

The Bizzarrini GT 5300 (aka Iso Grifo A3) has been one of the most under appreciated and least understood cars in history – until recently, but yet the technical genius of Giotto Bizzarrini is not fully understood by all. In this article the author will try to share the brilliance of the aerodynamic design of the Bizzarrini GT 5300 Strada.

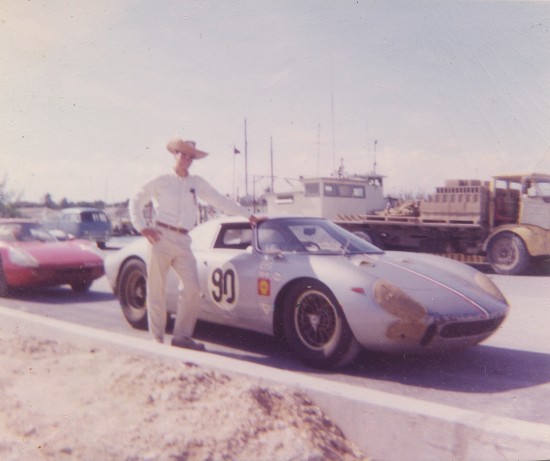

Ken Phillips was the original owner of the 1966 Bizzarrini GT 5300 Strada chassis no. IA3*0256, which I also owned for many years. Ken bought this special Bizzarrini new in Italy and shipped it to the US where it has remained ever since.

Here he shares some of his knowledge about the Bizzarrini GT 5300 Strada aerodynamics gained from his years of driving and studying this special automobile.

Every air vent, every opening and every body contour on the Bizzarrini GT 5300 is there for a purpose and that purpose is to win races. It also just happens that it is beautiful to look at as well.

Text by Ken Phillips –

I have spent many hours under the hood and sitting under Bizzarrini GT 5300 Strada No. 256 when it was up on the lift using my wind tunnel experience (when I worked at Boeing) to try and “see” the air flow over and under and even through this car.

Maybe Ing. Bizzarrini saw it when he created each of these advantages. I understand he studied aerodynamics at university and at Alfa Romeo. But I believe he could “see” it.

New things like serious front “spoilers” to me, air dams to others, rear spoilers and even wings at the rear and the under car rear diffusers are all a long time away in the early 1960s.

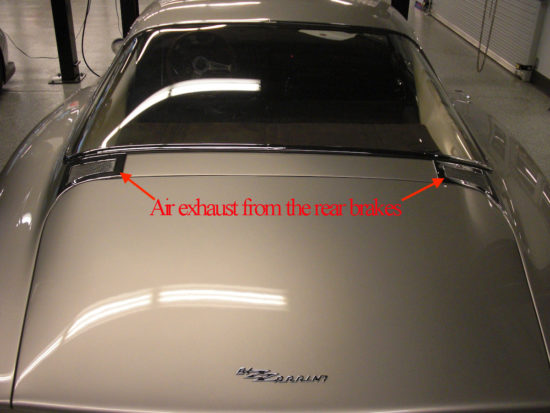

Bizzarrini’s large twin air scoops under the center of this car to get the building air pressure lift and drag out from under the car and put it to good use in both cooling the inboard rear brakes and in decreasing the very strong air flow and lift over the top of the car and down the rear window and deck to “pull” that already fast moving hot air up and out of the two upper rear vents, which are behind the rear window.

I have seen some mechanics working on Bizzarrini cars install front facing scoops behind the rear windows trying to push air back down those ducts to cool the rear brakes. They did not understand Bizzarrini’s intention here. If those under car center scoops are still there or not, I doubt if air could be forced backward down those air vents through the body ducts to the rear brakes.

Bizzarrini GT 5300 Air Flow

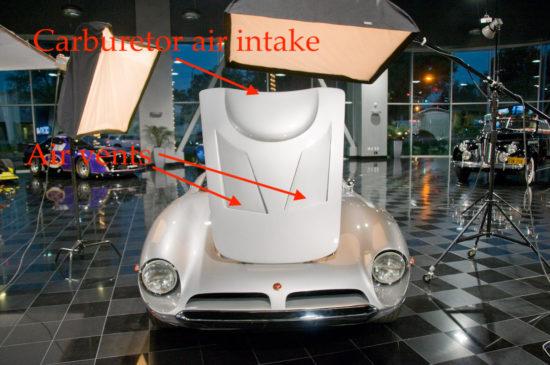

1. A carburetor air intake is facing backward on the hood from in front of the windshield. One of the first of this kind that I know of. It was years later that Roger Penski used that high pressure at the base of the windshield to flow air forward under the hood on Mark Donahue’s Trans Am Championship Camaro. Or the Rear opening “Shaker” Air Scoop in the hood of the High Output 1971 7.6 liter Pontiac Trans Am.

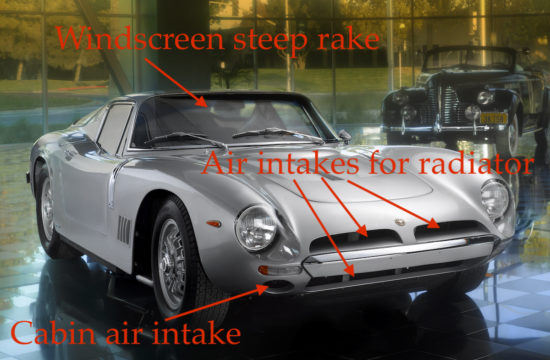

2. On the Strada the large air intakes under the headlights delivered air into the cabin for cooling the driver and passenger. On the Corsa they were used to cool the front brakes or to send cool air to the carburetors.

Many owners do not know that the best racing brakes need a certain amount of heat to function. Also many owners never found either of those outside air ducts that ended up under the dash just in front of their lap or the simple hand operated flap valve required to open or close each duct. If those ducts were fully open and the Bizzarrini driven at speeds for which it was designed the air flow through those ducts would be enough to blow your kilt up over your ears.

3. It has rear inboard disc brakes providing significant “unsprung” wheel handling advantages but it is very difficult to get cooling air to those brakes. The Bizzarrini had two large air scoops under the center of the car extending much of the width of the car. Each scoop shaped to change from a scoop to finish as a duct (like a funnel) to remove that high pressure air from under the car up and over those inboard disc brakes. Then the air flows into air channels continuing from above and behind the rear brakes and running all the way through the Bizzarrini body upward and out two vents behind the rear window exiting into the air creating suction at the body surface just below the rear window.

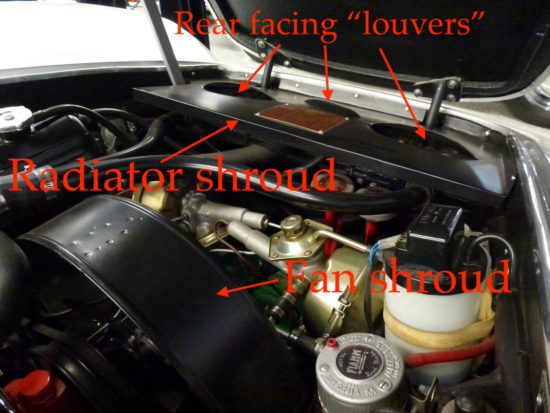

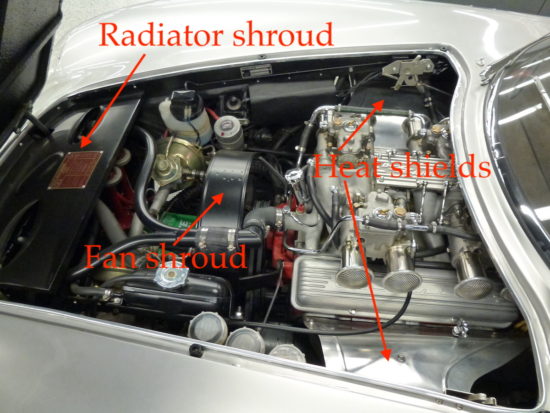

4. The engine radiator has a flat aluminum shroud with rear facing “louvers” that directed hot air leaving the radiator up and out functional open slots, in the forward part of the Bizzarrini aluminum hood, into suction of fast flowing air above, but not touching the surface of the engine hood. This reduced the amount of hot air going directly into the Webber carburetor intakes.

5. This same radiator shroud extends backwards into the engine compartment toward a large engine fan (these radiator shrouds and fan shrouds are now missing in many Bizzarrinis) that extend backward to the engine, which is very far back and low in the frame. That fan is unusually far back from the radiator that it usually serves.

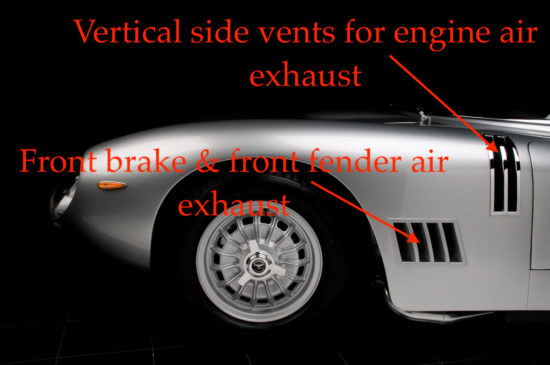

6. The two aluminum heat shields on each head have insulating material between them extending from the length of each head immediately under the lower side of each valve cover, up and over the headers all the way over to the inner fender well on each side and out the vertical side vents. Those vertical chrome vents are far back on the front fenders of the car because of the extreme rear placement of the engine.

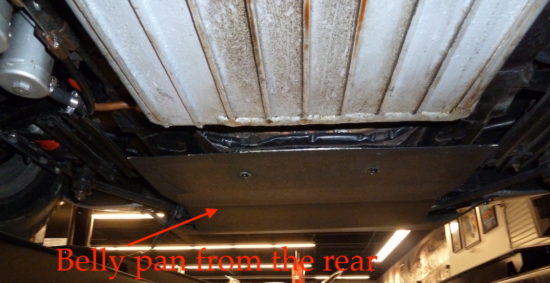

7. Under the front of the car running from the very front backward toward the front of the bottom of the fan was the first 1/4 belly pan that I had seen. It was years later that I saw these 1/4 belly pans used on other cars such as Ferrari and front engine Porsches.

The combination of the lower belly pan, the upper radiator shroud and the header heat shields all contributed to directing the hot air from the radiator and engine and exhaust headers all the way through the extended engine compartment out through the chrome vertical vents in each side of the body at the rear of each front fender.

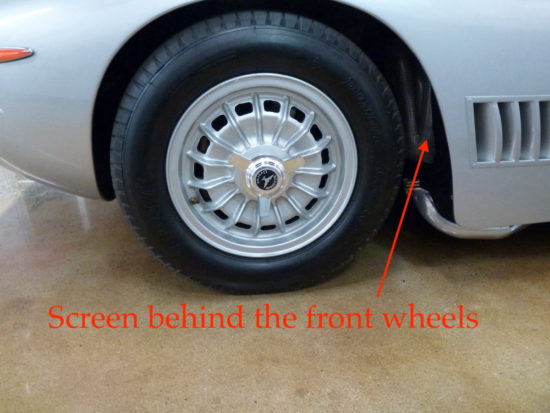

8. These chrome air vents on the front fenders are not the same, or part of, the body color vents in the front fenders behind each front wheel. There is a big opening with a grille in each fender well leading to those painted vents. I have seen these vents removed and accidentally reinstalled backwards. I was standing next to Ing. Bizzarrini when an owner of an especially fine Bizzarrini, but these vents had been put back in backwards after an excellent repaint, asked Bizzarrini which way the vents should point? Bizzarrini not wanting to hurt the owner, (by way of his interpreter) said they were all right. These ducts are to remove both the hot air from the front brakes and the normal very high pressure air under every front fender causing front end lift.

All race cars today have some method of getting that air out from under the front fenders. Now usually just slots in the top of each fender. But those slots exit all trash and water spun up and out by the front tires over the rest of the car, so not as desirable as these side vents on the road.

9. Behind each rear wheel are open vents with a grille that removes the high pressure air lifting the rear of the car.

10. The unusual flat sides of the body are also aerodynamic advantages. The slab side Bizzarrini GT 5300 may be the first, or one of the first, cars designed this way for aerodynamic advantages.

11. The overall low profile, shape of the body (including a Kamm Tail) and windshield added to these other creative features were a big aerodynamic advantage over the Ferrari 250 GTO. The Bizzarrini GT 5300 was specifically designed to race at Le Mans.

I do understand that having a Bizzarrini available with the hood open and a lift to inspect the underside is helpful to appreciate or understand the ideas expressed here and everyone does not have that opportunity.

Let us know what you think in the Comments.

Ken Phillips is a friend and the original owner of my former Bizzarrini GT 5300 Strada (Chassis No. 0256). He has been involved with fast cars and motorcycles all his life.

Thank you Ken, a great write up and explanation from a man who obviously understands these cars and why they were built like this. Not many do. Also, Giotto often changed the design of certain parts like the radiator and fan shroud after new (race) experiences. A true visionary.

Good to know there was a “form follows function” purpose behind all those vents & louvers. I saw one of these cars under restoration and noted that the vent louvers were made of brass, then chromed.

It seems that the red Bizzarrini in the third to last picture of your posing has an extra set of louvers on the cowl piece in front of the hood.

The red Bizzarrini fender you see in the photo you mention is a P538 not a GT 5300.

I think that this is the first time that I had seen the details under the car. Is that rear suspension also Corvette componentry?

No, the rear suspension is a De Dion. The differential is Salisbury with in-board disc brakes.

Ken, wonderful article, I hope you are doing well. Great explanation of the aerodynamics and cooling of the Bizzarrini

Brilliant !! Thanks !

Reads like an engineer’s examination of a captured MIG fghter. I had no idea that, under the beautiful body there is a lot of airflow ccntrol. Now I think Ing. Bizzarrini is even more of a genius!

Thank you so much for this amazing article it was very nice reading it. There is one thing that has been making me wonder for a while about the Bizzarini 5300 in general. Why did the normal cars use de dion at the rear end but the America version used a double wishbone setup at the rear instead of the de dion with 4 link. Wiki says it was to make it cheaper but double wishbone is generally regarded as a much better suspension geometry than de dion. So if double wishbone was cheaper already and in theory a lot better of a geometry, then why did Giotto Bizzarini used de dion at the back in the normal cars but double wishbone only in the America version? For example the ATG 2500 GT that Bizzarini also did before going to ISO, that car had double wishbone suspension at the back as well but for some reason he used de dion when making the ISO Grifo and the 5300.

When Giotto drove the Gordon Keeble with Renzo Rivolta he was impressed with the Corvette small block and the de dion rear suspension. He felt that with the torque generated by the engine this “semi-solid” rear suspension was perfect. Indeed, this system was grafted into the First Iso, the Rivolta GT, and all other Iso models. Giotto used the rear half of the Rivolta GT chassis for the A3/C and many of the first GT Strada/Corsa Cars under his name. The agreement between Giotto and Iso was that Iso would get the name “Grifo” and Giotto would get the needed parts to create 50 cars of his own. Obviously that was 50 chassis, engines, transmissions, de dion rear suspensions, front suspensions, etc. Giotto was underfunded, and home made parts cost less than purchased parts, so he likely went to the double wishbone setup because they were running out of de dion units.