by Mike Gulett –

History has a way of rewarding bravery late. The designers who push strongest against convention are often dismissed in their own time—their work labeled strange, impractical, or “too much.” But years later, the same ideas quietly reappear, softened, refined, and then celebrated. In hindsight, the verdict becomes clear: they weren’t wrong. They were just early.

A few designers stand out not just for boldness, but for how accurately they anticipated where the automobile style would eventually go. Their ideas didn’t fail; the world just wasn’t ready.

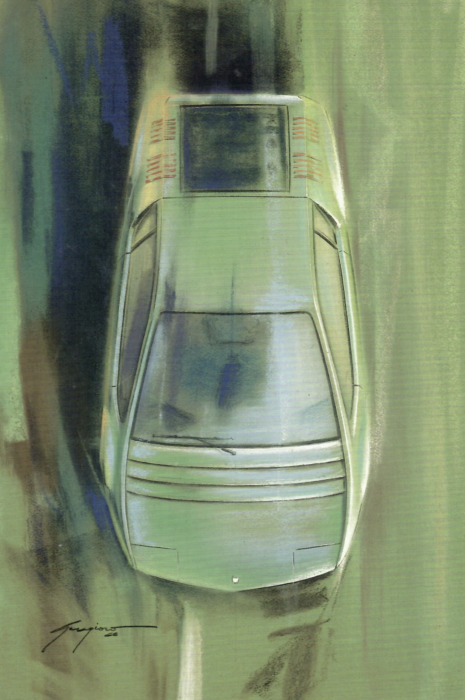

Marcello Gandini

Marcello Gandini is now revered, but during his most radical period he was often misunderstood. Working at Bertone in the late 1960s and 1970s, Gandini rejected flowing, organic curves in favor of sharp edges, extreme proportions, and dramatic surfaces. Cars like the Lamborghini Miura were sensual, but it was his later work—the wedge-shaped experiments—that truly unsettled people.

The Lamborghini Countach, with its origami shape and impossibly low nose, looked less like a car and more like a concept escaped from a design studio. Critics called it theatrical, impractical, and excessive. The Lamborghini Espada also drew critics who either loved it or hated it and that argument still goes on today.

Yet now, nearly every modern supercar owes something to Gandini’s visual vocabulary: the sharp creases, the rising beltlines, the sense that the car is carved rather than drawn.

Gandini understood a fundamental truth long before others — once performance reached a certain threshold, cars would need visual drama to communicate their purpose — speed alone and engine sound would not be enough. Shape would become an importance part of the storytelling.

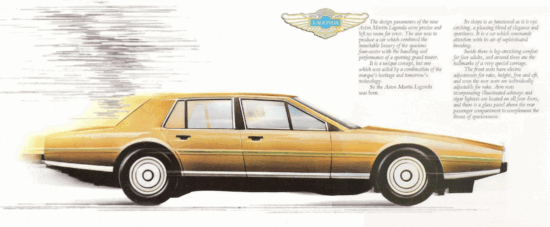

William Towns

In the 1970s, William Towns seemed almost antagonistic toward traditional automotive beauty. While others chased elegance, Towns embraced flat planes, right angles, and brutal simplicity. His most famous work, the Aston Martin Lagonda, looked like a spaceship parked among luxury sedans. This is another design that is either loved or hated.

At the time, it baffled buyers and critics alike. Too angular. Too electronic. Too strange. The Lagonda felt disconnected from Aston Martin’s heritage, and many dismissed it as a curiosity rather than a direction.

But Towns was designing for a future where aerodynamics, packaging, and technology would dominate aesthetics. Today’s luxury sedans—low, wide, aggressively geometric—would look far more familiar to Towns than to his contemporaries. Even the modern fascination with full-width lighting, minimalist surfaces, and architectural interiors echoes his thinking.

Towns wasn’t rejecting beauty. He was redefining it as something colder, sharper, and more intentional.

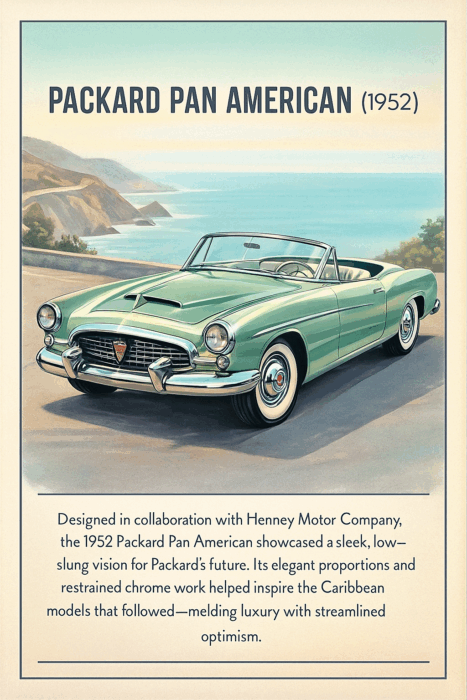

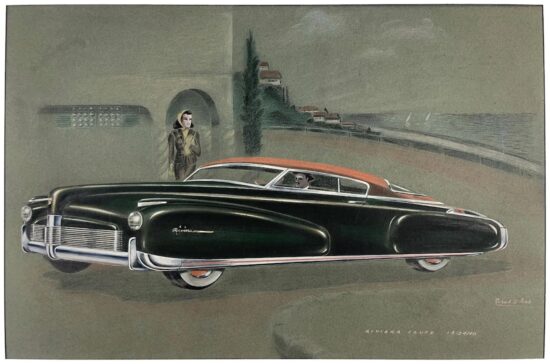

Richard Arbib

Richard Arbib’s designs often looked like they were moving fast even while parked. Influenced by aviation, space exploration, and the optimism of postwar America, Arbib infused his work with fins, scoops, and dramatic forms that suggested speed and the future.

In the conservative 1950s and early 1960s, his ideas frequently went too far for production realities. Cars like the Astra-Gnome concept felt more like rolling science fiction than consumer products. Critics admired the imagination but doubted the practicality.

Yet Arbib grasped a psychological truth that modern designers rely on: cars are emotional objects first and transportation second. Buyers don’t just want efficiency—they want to be inspired. Today’s hyper-styled electric vehicles and concept-heavy production cars echo Arbib’s belief that drama sells the dream, even if the reality is mundane.

He understood branding before branding became a science.

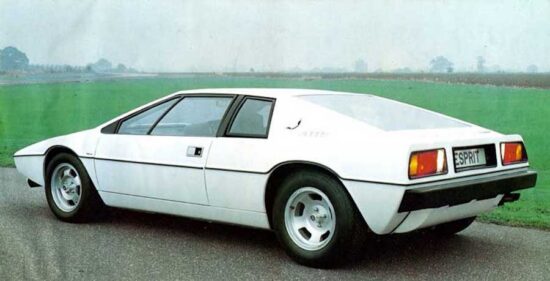

Giorgetto Giugiaro

Unlike some of his peers, Giorgetto Giugiaro’s genius wasn’t just in the exotic. It was in making radical ideas feel normal. Cars like the Volkswagen Golf and Lotus Esprit introduced clean, functional design that initially felt stark compared to the curves of the era.

Early reactions were mixed. Some saw the simplicity as dull or overly industrial. But Giugiaro’s designs aged better than most designs from their time. His understanding of proportion, ergonomics, and visual balance anticipated the modern car’s need to be timeless rather than trendy.

In an era obsessed with ornamentation, Giugiaro trusted restraint. The world eventually caught up.

Why Being Early Can Look Like Being Wrong

Designers who are right too early share a common problem: they expose the gap between what people want today and what they’ll accept tomorrow. Radical ideas challenge comfort, and comfort can be a powerful force.

Markets resist unfamiliar shapes. Manufacturers fear risk. Critics judge based on present taste rather than future relevance. And so, the boldest ideas are often softened, delayed, or shelved—only to reemerge years later under different names and different badges.

Often by the time the world embraces these ideas, the designers themselves are gone, their originality diluted into mainstream acceptance.

The Quiet Vindication of Time

Time is the ultimate design critic. It strips away fashion and leaves only the designer’s intent. When we look back at Gandini’s wedges, Towns’ angles, Arbib’s motion, or Giugiaro’s clarity, we don’t see mistakes—we see blueprints for the future.

They weren’t chasing trends, they were predicting them. Their work was not appreciated immediately, but it became inevitable.

Are there other designers who should be on this list?

Let us know what you think in the Comments.

Research, some text and some images by ChatGPT 5.2

Speak Your Mind