Yes, Shelby’s family sold it.

by Wallace Wyss –

I suppose a lot of inventors sell the first of something they create but you gotta hand it to Carroll Shelby, he hung onto that first Cobra through thick and thin.

Did Henry Ford keep the first Model T? Enzo Ferrari the first Ferrari? I dunno, I just know that in the beginning years of Shelby American Carroll Shelby must have been awful tempted to sell that first Cobra, if anything to be able to fund a better wardrobe for when he flew to Dearborn to deal with the Ford executives who signed his checks.

Shelby built the right car at the right time. Only ten years before this 1962 Cobra he had first belted himself into a race car. His rise as a driver was meteoric, by ’53 he was racing on International teams.

In 1959 he won the 24 Heures du Mans in a British sports car, an Aston Martin with co-driver Roy Salvadori.

It was while racing in Europe he took further note of the lower price sports cars, as he harbored the ambition to build his own car. In order to do that he had to sample every kind of car he could, from the MG TC to the Porsche Speedster.

Mostly he cadged sponsored rides in the expensive cars–Ferraris, Aston Martins, Maseratis, only occasionally did he dip into the common machinery. He even drove an experimental Corvette, the SR2, a race car that was built just before GM outlawed racing tie-ins.

His racing career was built on perpetuating the idea that he was healthy but ironically he had a bad heart and had to pop nitro pills just to get through a race. At his last race, he took at least seven and that wasn’t doing it so he stopped during the race, took off his helmet and quit racing on the spot.

It was pretty close to the AC Ace which AC continued to sell while Cobras were in production – courtesy RM Sotheby’s

He wanted to build a car that was raceable but he wanted to keep expenses down, which meant not making his own engine. He had seen at least three other Americans try it, one being rich playboy Lance Reventlow, who had spent a fortunate on his Chevy and Buick-powered sports cars. Another being Briggs Cunningham, putting Chrysler engines into various cars and even racing Cadillacs. In fact, Shelby raced a Cadillac-powered Allard. Sure the American engines with their iron blocks and iron heads and pushrod valve trains weren’t as sophisticated as Ferraris or Maseratis but dammit, they were dirt cheap to run.

After he quit racing, he sat around the apartment and tried to think of a way to mint money. One idea was a School of High Performance Driving, at Riverside Raceway (where he employed a youthful instructor, Pete Brock, who would be of immense use later on).

He would advertise the school in Sports Car Graphic and got to know one of the editors well. It was at lunch with that editor that he heard that AC Cars Ltd, the makers of a British sports car called the AC Ace were losing their supplier for Bristol engines.

He managed to call up AC and hornswoggle a car, engineless, and then called Ford, who he had heard had a small block 221 cu. in. Ford V8 (the Falcon V8). Ford thought AC was backing him. AC thought Ford was backing him. Actually nobody was backing him. But he got that engine put in that car and that car became the first Cobra, CSX2000.

The first engine had a been a 221 incher but soon Ford had graduated to a 260 cu. in. version and they sent that to Dean Moon’s shop where Shelby got that engine put in instead.

They drove it around the oil derricks nearby and saw it had a lot of potential.

Shelby then called for a meeting with Ford executives at the Ford World HQ, “the glass house” in Dearborn, where he presented his case, that Ford ought to back his creation.

As it happened, Ford had just started a sales campaign called “Total Performance” to market the high-performance 260 V-8 in the Falcon This may have been the famous meeting where Lee Iacocca told his fellow execs “Give him $25,000 before he eats the curtains.

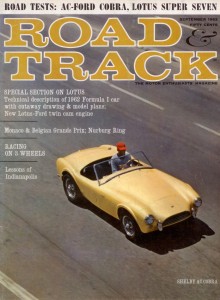

Shelby went home to California and began promoting the car with magazines. He talked Dean Jeffries, a customizer, into repainting it every few weeks so folks would see a yellow car on the Road & Track cover, a blue one on some other cover and think these Cobras must just be rolling off the assembly line.

Shelby even had it sanded down to bare aluminum, and oh, once production started would pry off the AC insignia on the hood and put on his own Cobra logo.

Car and Driver said it best, in summing up the car,

The Cobra is a shockingly single-purpose car. No frills, no extra sound deadening, only the implements (tube frame, four-wheel disc brakes, fully independent suspension) required for rapid transit. The flat instrument panel has single white-on-black gauges – one to monitor every factor you might need to check, including oil temperature. The external body sheet metal extends right into the cockpit to form the top of the instrument panel and the windshield clamps down on the cowl, in traditional British sports car fashion, just inches in front of your nose.

In light of the way the press hammered the car, it is amazing CSX 2000 lasted those first five months, before Shelby got another car.

So the second and third car were built. The only big change was the moving of the rear brakes to outward, easier to change in a race, and making the trunk lid shorter to strengthen the body.

The car was used at the Carroll Shelby School of High Performance Driving. It has made many appearances in the past 50 years.

Its last color before going to auction was a deep metallic blue. The upholstery was a bit raggedy, but the car is a living testimony to how much a car can change from is first incarnation. Shelby told Motor Trend “. . . we strengthened the chassis tubes, we had to put different spindles and hub carriers on it, we had to put a different rear-end in it . . . there were very few nuts and bolts in that car that were the very same nuts and bolts as in an AC Ace.”

So at some point the car metamorphosed into the Cobra.

The name came about, Shelby claims, as a result of a dream. He woke up and wrote it down. He had to pay some small company money to use it as they had copyrighted the name for their copper-brazed engine (COB-RA).

Even the auction company, RM Sotheby’s waxed eloquent about the car, saying

Ultimately, no degree of hyperbole could ever truly summarize CSX 2000’s monumental importance to the automotive industry. Had it never been built, had it accidentally been crashed by an employee or even a journalist, the impact on Shelby American would have been clear: 289 Cobras would not have gone on to dominance in the USRRC and SCCA Championships, nor on the international stage that was the FIA World Sportscar Championship, and specifically the 1965 24 Hours of Le Mans. Certainly there would never have been any 427 Cobras, or any of the tremendously successful GT350 and GT500 Mustangs that followed, including, of course, the cars that won the SCCA B-Production.

It was the success of the Cobra that got Carroll Shelby the job in 1965 of taking over the running of the Ford GT40, which led to the defeat of Ferrari at Le Mans in 1966.

After Shelby’s death, the family, taking stock of the many cars he had left behind, decided it needed to go. The car sold for $13,750,000 in 2016 at auction in Monterey.

Hey, not bad for a used car….

Let us know what you think in the Comments.

THE AUTHOR: Wallace Wyss is a biographer of Carroll Shelby. His paintings of Cobras and GT40s will be at his Art & Books booth at Concorso Italiano at Monterey this August.

This photo of CSX 2001 (the first production Cobra) and Bruce Meyer, the owner, was taken by me in his garage.

Shelby Cobra CSX 2000 on display at Laguna Seca in Monterey, 2012 – photo by Mike Clarke

it’s the fairlane 260 not the falcon 260 the 221-260 was in the fairlane in 62 wasn’t in the falcon until 63, 221 was never in the falcon