Review by Wallace Wyss –

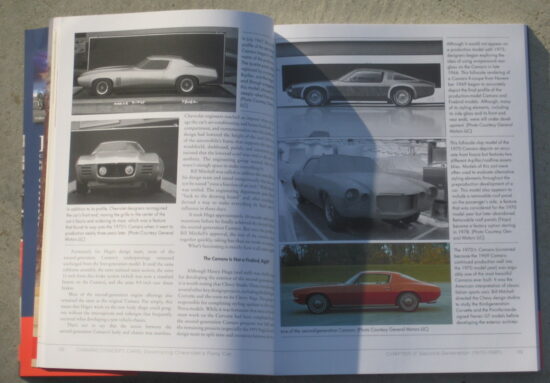

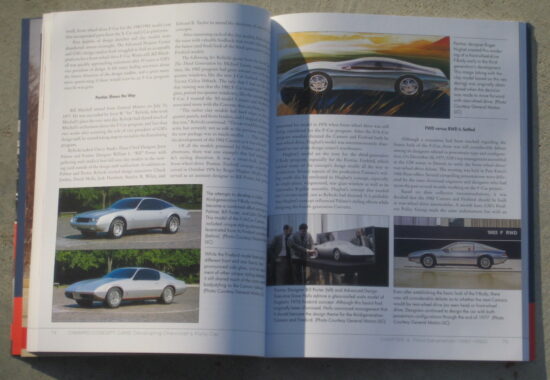

Title: Developing Chevrolet Pony Car Camaro Concept Cars

Author: Scott Kolecki

Publisher: Car Tech

Pages: 176

Binding: Soft cover

Books on concept cars are the new new thing. True, in the past, car histories, including many of my own, there’s a couple references to a concept car that led up to a production car but this writer, Scott Kolecki, is diving deep into Chevy’s pony car, generation by generation, relating which concepts led to which production cars.

And it’s very entertaining. It reminds me of those books on movie stars where you see, for instance, Marilyn Monroe, still with brown hair. You wonder, if she hadn’t gone blonde, would there eve have been Marilyn Monroe the movie star?

But I digress. The beauty of this book is it shows how creative the American car industry can be; and it’s almost sad that some of the Camaro prototypes are breathtakingly beautiful,; and yet they got rejected because it would have cost $12 more a car to make the roof angle this way instead of that way.

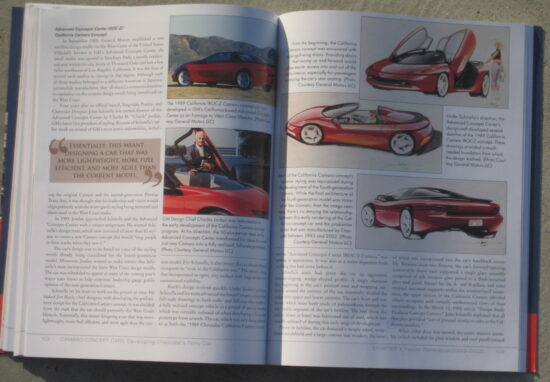

One of the undercurrents in the book is the zeal to get better mileage was stalking the Camaro from its first inception. Chevy wanted a performance car to counter the Mustang, which was a hit from Day 1, but there were times in its history when it got a V6 instead of a second V8 offering because they knew that the great Oil Embargo was coming. There were even times when they debated putting the Camaro body on a smaller lighter chassis and not even offering a V8.

Same argument on front wheel drive. Some saw the success of the European and Japanese front drive threatening the heavier American cars with an engine up front, a long heavy driveshaft and differential in the rear. Yet there was a “muscle car” contingent always in the Camaro’s corner fighting to keep it rear wheel drive and V8 powered no matter what happened with fuel supplies.

What is really mind blowing in the book is the creativity afforded the designers in the early stages of each new generation—some of the best designs in the book are done in those conceptual stages. Then, as the clays march on, you see them lose this clever touch—say a plexiglass hood scoop with carbs showing a la ‘50s Ferrari Testa Rossa—and that one because it would have added a few dollars to each car and we are talking volume of over 100,000 units a year at times.

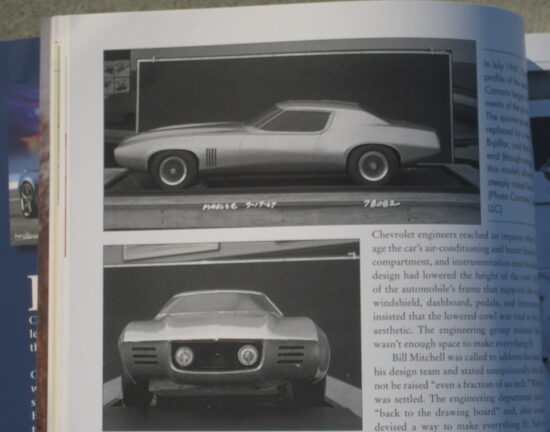

The author is pretty straightforward, recounting chronologically what happened as each design progressed, and giving credit where credit is due. But there’s little hints of internecine warfare among the design groups, like sometimes an Advanced Design group would set up a design studio across the street from the GM Design Center and work on a design on their lunch hour and after hours.

Bill Mitchell, the Styling boss at GM at the time the Camaro was born, with a career going back before WWII, emerges as the stalwart warrior who wanted performance, and throughout the book you see his own “concept cars” built just for him, and there’s stories of his epic battles with management. He told me once he liked to hire designers “with gasoline running in their veins.”

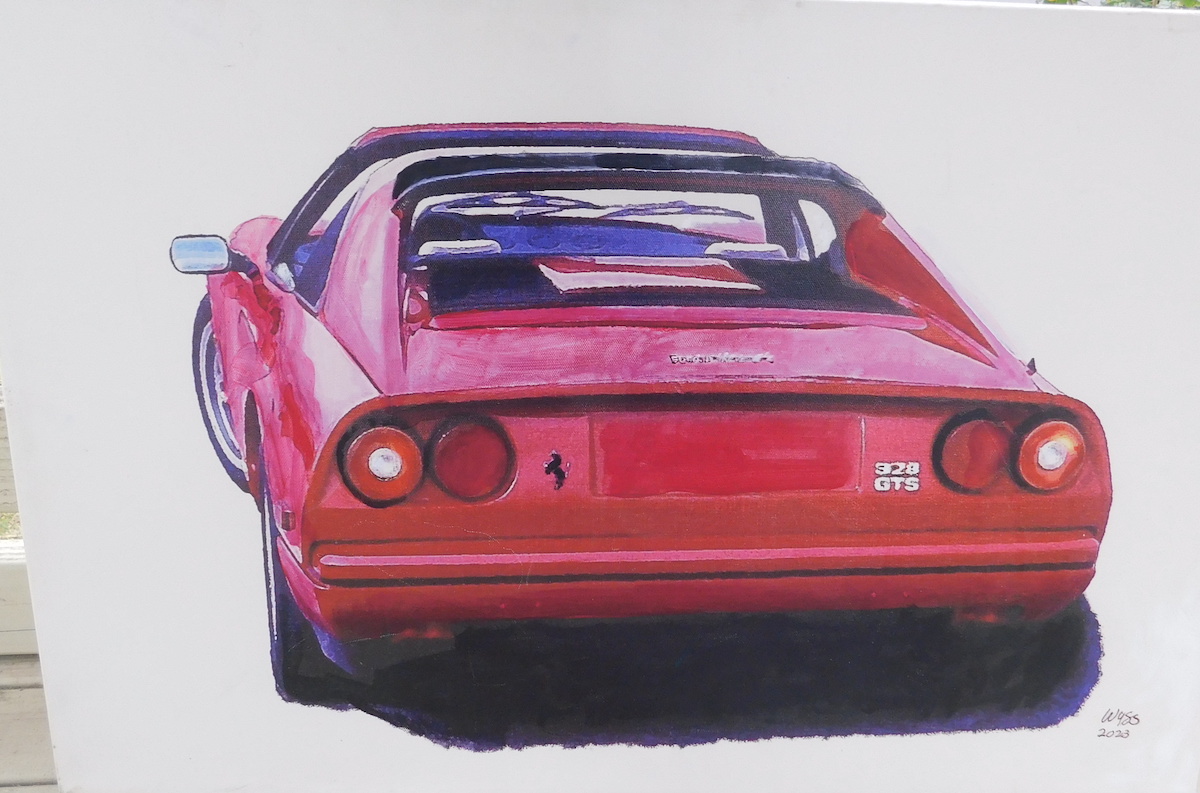

One thing that received no mention at all (and perhaps the author not being from Detroit, he didn’t know of it) was the personal cars owned by some of these designers, sort of an ”underground” of connection to European designers. Naturally at that time even if you could own a Ferrari you didn’t drive it to work because GM stalwarts would conclude your heart was with the Ferrari prancing horse not with Chevrolet’s bow tie. I knew about their private cars because I grew up in Detroit, went to parties where people like Hank Haga would show their gullwing or there was an AMC engineer who among his Ferraris owned a fabled Ferrari 250GTO.

In fact nowhere in the book does he say “And this taillight was clearly inspired by the Maserati Ghibli which came out two years before, etc.” as if all these European inspired designs came out of nowhere.

GM was very loose on nailing down some hard and fast rules what happens to concept cars after their show career is over. Repeatedly you find that it went into storage; were crushed or, whatd’ya know was auctioned off, despite the fact many did not have the proper safety equipment or engine emissions, because after all they were built for showing (internally as part of the design process) or at auto shows.

The last chapter shows when GM realized it could make limited editions of show cars and the author just slam bangs one description after the other, and I consider those worth mentioning, but at conflict with the main theme of the book which is to show where the ideas came from and how they evolved into a production car.

One particular car called the Camaro Europa Hurst, I didn’t think belonged in the book, but hey it had a Camaro chassis so I shouldn’t complain. It was such a bland car that I wasn’t surprised when it did reach an auction, it sold poorly, and kind of knocks the comment “They should have gone to a European designer” out the window because the American concepts are so much better (but then that particular car was done at the end of a European designer’s career when he was perhaps out of touch with current trends).

Really titillating for me was the hints here and there of conflict, like when Chuck Jordan (who violated that rule of what you drove to work by driving Ferraris to work starting with his 250GT Lusso) coming in and telling another designer to start over on the rear of the car or start from scratch. The political battles are hinted at and now, all these decades later, I am sad that when I met these people (even going to Mitchell and Jordan’s homes) I didn’t ask more about the battles for a certain design.

So in sum, this book is most of what I was hoping for—GM (and some of the other automakers) are finally releasing the old photos of clay models and some original drawings so we can see where a car we love came from. And it’s sad because of the low price of the car compared to European exotics, so much that could have made the car better was rejected because of a $10 additional cost here or a $12 additional cost there.

I go back to the Marilyn Monroe example—so many of the cars in this book are stunning—but your realize how ephemeral the whole design process is—one exec doesn’t like blondes so she stays on the factory assembly line (that’s where Marilyn was supposedly discovered, when a photographer picked her out to portray as a Rosie the Riveter type). And a whole section of movie history doesn’t happen. I think this book shows we as Americans had the talent, but it just didn’t surface in the production models as much as it does in these concepts…

Let us know what you think in the Comments.

THE AUTHOR: Wallace Wyss is the author of 18 car books. Presently he comments on car design on the radio show Autotalk, broadcast weekly on KUCR FM radio.

Thanks for the great book review, Wallace. Your personal perspective on knowing the people involved is always interesting. I would love to get that book. My best friend’s parents when I was growing up purchased a brand new 1967 Camaro convertible. It was white with a stripe around the nose, had a black convertible top and small block V8 in it. I loved that car! My parents purchased a brand new 1972 Camaro at the dealer in San Rafael, CA. I remember going to the dealership with my dad the day he ordered the car for my mom. He wanted the V6 to my horror and by some sort of miracle, got him to order one with the 350 V8 in it….column shift unfortunately, but you have to pick your battles! I bought the Camaro from my parents a number of years later and the car is shown here. I swapped out the standard wheel covers my dad got for the “fancy” turbine style covers shown, which was an extra cost option on the Camaro and the Corvette. I purchased these wheel covers from “Hub Cap Johnnys” in San Carlos, CA, south of San Francisco. Icing on the cake. In any event, neat to have some back story on the development of the Camaro and what could have been.

Here is a photo of Rob Krantz’s Camaro.